Click below where you can download Aaron Garcia University Doctoral Thesis:

—-Tesis Doctoral Aaron Garcia Granada Escuela antigua de construcción de guitarras.

Doctoral Thesis Aaron Garcia Old Granada Guitar Making School PDF—-

This is a 1797 guitar by Juan Pagés made in Cádiz,\Na very old guitar that I have been restoring for some months.

A guitar that was in very bad condition and we are\Ntrying to follow the most current system of restoration

and that follows, so to speak, the dictates of the\NInternational Institute of Museum Conservation.

From ICOM. With materials as similar as possible

to the original and without trying\Nto falsify the parts, but to try to make it noticeable

clearly which part is not original.

That’s fundamental. That when\Nsomebody sees, some expert sees the instrument,

then they know which parts are original and which parts\Nare the parts that I have replaced.

Juan Pagés is perhaps the initiator of the very famous\N18th century Cadiz school. He was born in a village

of Seville. He was already building guitars there. And he moved\Nto Cadiz, which was where the contracting house was.

He started to make some guitar models that were very advanced\Nof the time compared to what was being done in Europe.

In history he is a very important figure.

In the history of the Spanish guitar.\NHis brother or his son, that’s up for debate,

his brother is José Pagés, from who are preserved many more

instruments

And then there are also other family members who also\Nbuilt guitars at the end of the 18th century.

and early 19th century

The fan bracing system,\Nthe internal bracing of the guitar is made

There are already some guitars made by Sanguino de Sevilla\Nwhich had a fan bracing system on the top for reinforcement.

but they make this system very well known.

For example, Panormo’s 19th century English guitars.

are very much influenced by this model of\Nguitar. And then also, not only the ones

from Panormo, also in the USA,

Martin’s guitars are also very,\Nvery similar to this model of guitar.

Well, they don’t really have much in common,\Nthe Pagés worked together with other greats

makers like Benedict and Recio in Cádiz. And\Nthey may have had an influence on the Sevillian school.

When Torres arrived in Seville in the middle of the 19th century.\NBut by then the guitar had already changed a lot.

I think that the Pagés are an earlier\Nprevious generation

and their guitars have a different structure.

But, for example, the use of\Nnoble materials like the Brazilian Rosewood\N(Dalbergia Nigra)

and spruce tops of very good quality.\NVery low weights, very light guitars.

and of course the fan bracing system.

Torres does not rely directly.\NTorres learned

to make guitars probably in Granada

in the fourth decade of the 19th century, and then moved to Seville.

This is what the priest Sirvent already said in a letter, a famous\Nletter that reflects Romanillos in his book that Torres told him

that he made his first guitar in Granada.

And then there are many authors of the period and\Nimmediately afterwards. Like Pujol,

like Domingo Prat, who say that Antonio de Torres\Nwas a pupil of José Pernas here in Granada.

We did not find any data on this relationship

master and disciple.

But the guitar, the constructive style and the secondary sources\Ndo speak to us.

speak of this relationship. For example, Domingo Prat in his\Ndictionary of guitarists, says it on up to five occasions

that Antonio Torres was a pupil of José Pernas.

And it’s not the only basis.

So, I believe that Antonio de Torres is based\Nmore on the Sevillian school when he arrives at

Seville in the 19th century, and what he learned in Granada.

And possibly some notions that he had earlier\Nof Almeria.

More than on the models that by that time were already\Nwere a bit obsolete, which the Pagés had made.

The Pagés almost always worked with six double courses strings.

So they were making the model that I call the\Nneoclassical guitar and what Romanillos calls vihuela.

Well, I think something Torres actually invented…

in fact he didn’t invent anything.

All the innovations\Nthat are usually attributed to Torres

had already been done before by some guitar maker, both in the size of the body\Nand in scale lenght..

In the type of bridges, in the use of mechanical tuning pegs, even in the\Neven in the bars systems, we can say,

that except for the floating harmonic bar\Nused by La Leona on which the fan struts

pass underneath that bar, which then became\Nworld famous as the Bouchet system,

except that, I think that’s an innovation of Torres.

But everything else

some guitar makers has done it before.

But the great importance that Torres has is that he knew how to\Nperfectly understand all the innovations

are taking place in the schools of Granada, Malaga,\NSeville, Cadiz and group them together in a model of instrument.

that from that date onwards will be copied by all the guitar makers.\NAnd a few decades later, all of Europe.

And we can say that even today\Nthis model is still being copied.

The classical guitar model.

I think the biggest influence may be in the ornamentation.

in the design of the head on the guitars.\NLaprévote and Lacote used to make a trilobed design

and then it was used here in Granada

by José Pernas. There is a guitar by José Pernas dated 1851\Nwhich already has this trilobate motif and which is

a stylisation of the trilobulates\Nused by Laprévote and Rene Lacote in France.

This is a copy that I am making of a guitar by José Pernas\Nthat is currently in the

collection of Jesús Bellido. It was previously owned by Marcelino\NLopez Nieto. This Pernas is probably earlier than the guitar La Leona

by Torres, the most famous guitar in the world. And which has\Nsome characteristics that we could say that

are predecessors of La Leona de Torres. Such as,\Nfor example, the three-part background, the 650mm scale lenght,

the slightly larger size than the previous guitars…

We are talking that this Pernas guitar is from\N1851 and La Leona is from 1856.

The top is perhaps what makes the difference between them because

Torres uses in La Leona a tornavoz, which is a kind of brass cone\Nthat is glued on this part

and which remains on the inside of the instrument.

This is the copy of the top of Pernas’ guitar,\Nwhich, curiously, has a fan bracing made in struts pairs.

Normally they tend to be in the majority of instruments

usually has an strut in the middle\Nand then struts on the other both sides

There are some guitars by Torres\Nthat also has this struts system by pairs.

So there’s quite a lot of relation. And another\Nrelationship that we can also make

approaching the French guitars, which is the rosette.

This rosette of Pernas’ guitar is exactly the same as\Nthe rosette of La Leona by Torres.

And this type of rosette had also been made\Npreviously in France by several makers.

Now that we’ve talked about the tornavoz, uh, I think it’s\Npossibly that the Tornavoz is also an invention of Torres.

I’m convinced that it’s Torres’ invention, although\Nwe know that Pernas also used it and that there were many other makers

immediately after Torres who used the tornavoz.

ok,

The oldest guitars…

Well, there are practically none of them\Nleft

but the medieval guitar was actually a small lute.

I can show you here I have a\Nreconstruction that I’m making of

a medieval guitar.

It would play like a lute

With a plectrum, and it would have double courses of\Nstrings. Three or four double courses.

and pegs in the style of the medieval lute.

But it was already called at that time

“guitar” here in Spain.

Also in France and in Italy.

It’s what we now call medieval guitar.

We’re talking about the 14th-13th century and there’s only one\Npreserved in Germany. By Hans Oth (1450)

From this point on the\Nthree or four courses guitar

and with a curved back,

we can say that it disappears, and appears\Na new instrument with flat back.

And with four courses of strings.

That’s seven pegs; one single first string, two second strings,\Ntwo thirds, and two fourths, four courses.

and suddenly they call it a guitar.

What we call a renaissance guitar

This instrument was probably born between\NValencia and central Italy, that is to say,

what was the kingdom of Aragon at that time.

That’s when the instrument began to be called guitar.

And at one point there is a famous poet, priest\Nand playwright from Ronda called Vicente Espinel.

by who is celebrated next year

the 400th anniversary of his death,

What did he add to that guitar? we’ve said before\Nthat already the guitar has a basic structure

with seven pegs and with a parallel back and top.

Then, this poet adds a fifth string to it.

A fifth course.

In the treble part to increase the possibility of playing\Nmore pieces, more possibilities

technical, above all. So this instrument\Nis what normally we know as baroque guitar,

that instrument, it starts to be called in Italy, in France and\Nother countries… it starts to be known as Spanish Guitar.

Learning methods were made, they were printed,\Nit was very successful and it was exported to France.

In France they also build\Na lot of this instrument

and it’s what we know as the\Nbaroque guitar and at one point already

in the second half of the 18th century

Approximately around 1770

there is a very important figure who is José Contreras,\Nborn in Granada and who worked in Madrid.

The most important luthier in the history of Spain.

He made violins, violoncellos…

So he’s quite an important figure\Nbut he’s practically…

we don’t know anything about him,\Nonly that he was born in Granada around 1710.

He married in Madrid.

His son was also dedicated

to the construction of instruments

In fact, on the label his son said “El Granadino’s son”.\Nto see how famous his father was.

He made some violins, above all, some very good violins.

And those violins are preserved

made by Jose Contreras. And one of his guitars is preserved.

which has 14 strings.

Seven double courses or having six\Ncourses in which the first and second orders were triples.

which was an arrangement that was also,

shall we say, a bit common in the 18th century

And we don’t know if he was the one who decided\Nto put six course like the guitar today.

Six course to the guitar.

But the oldest data of a guitar from 1760

where in a Madrid newspaper a guitar by “El Granadino” is for sale\Nwith six courses of strings (Jose Contreras guitar)

This is the first piece of information we have.\NUntil then they always had five courses of strings.

This was also widespread in Europe.

It caught on very quickly.

There were also some cases of seven-course guitars,\Nbut that wasn’t so successful, but actually

the guitar is this guitar that we’re talking about\Nwith six course (double strings)

The next evolution was from\Ndouble strings to single strings.

For tuning reasons, for playing possibilities,\Nof technique, of getting strings that match tuning better…

it was also an innovation that can have a basis in the\Nlyre guitar of France.

the neoclassical lyre-shaped guitars.

And also in the Italian and\NFrench theorboes … which also had single strings.

So maybe that’s what influenced\Nthis 12-string guitar to be

made the strings be single strings

The oldest ones we know of are in Italy.

Fabricatore and other makers.\NAnd also in France it was made

The oldest data we have about single strings guitars in Spain\NI think it’s in Ronda in a text by a writer

where he talks about a guitar that had\Nonly six single strings

And then we have also about the same date,\Nin 1803 the guitar maker from Granada, Agustín Caro

makes a guitar with three single strings.

This is the oldest surviving guitar with single strings.\NIt was in the collection of Angel Cañete.

and is now in an Italian collection.

But it is the oldest surviving example\Npreserved example of a guitar with single strings.

Later, many of these guitars, for example, by José\NPagés, Juan Pagés and other makers of the time,

what they did was to leave three strings on each side,\Nthree pegs, and cut off the head.

A lot of guitarists had this modification done

for use with the new fashion of single strings.

And that was something that in practically 20 years,\Npractically no luthier made double strings anymore.

All over Spain, all over Europe, all over the world, people are already\Nfrom double strings to single strings.

That was something that happened very quickly. And then also that time…

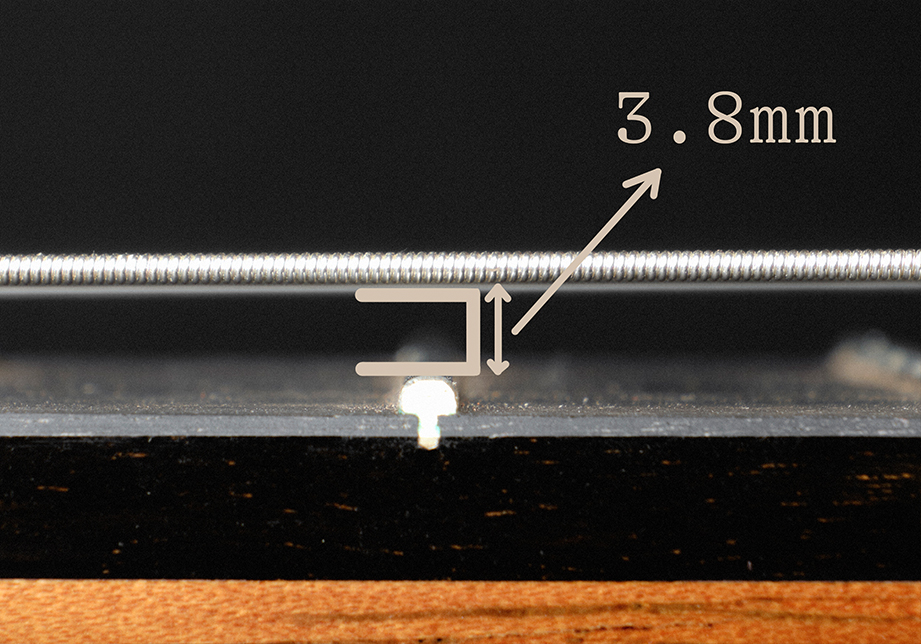

Because here we see that the fretboard

is in the same plane as the top.

And at that time, because.. also the earliest one\Nthat we know again is from Agustín caro.

He superimposes an ebony fingerboard on top of it. And it is an\Ninnovation that is also very successful.

And already all the makers who are after that time made it like that,

at least in Spain. In France for a few decades, they built with the guitar

with the top in the same level with the fingerboard.

But the Romantic guitar in Spain already has single strings, the fretboard\Nsingle strings, the raised fretboard ,

the bridge with the detachable bone,\Nmodern bridge.

Those are the features, that one, up to the Torres model.

When we talk about Torres and later on Santos\NHernández, we are already talking about the contemporary guitar.

There has no longer been any innovation that has been\Nspread among the makers since them.

Santo Hernández, possibly\Nthe best guitar maker in history.

Santos Hernández is\Nfundamental for the guitar.

And I would say that practically the whole of the Granada school of\Nguitar makers has its basis in Santos Hernández,

in the models of Santos Hernández. And they already said that

in the time of Benito and Eduardo Ferrer, and many guitar makers\Nfrom Granada have commented that they

copied, let’s say, followed, the models of Santos Hernández.\NManuel de la Chica, for example,

Manuel de la Chica guitar is a copy of Santos Hernández.

Santos Hernandez made a guitar a little bit bigger than\NTorres and he is the one who gives the actual dimension,

completely up to date. Because Torres’ guitars are usually\Na little bit smaller than the actual ones.

And Santos Hernández

let’s not forget that Santo Hernandez learnt,\Nwell, he was with Viudez and also he learned in

Rafael Ortega’s factory. Rafael from Granada.

Rafael and his father Francisco Ortega

were guitar makers here in Granada and moved to Madrid.

And they had a factory in the Placeta de la\NBerenjena which is at the end of Cava Baja street.

which is where Santos Hernández was born. Santos Hernández as a\Nchild would pass by almost every day, for sure,

by the guitar factory and\Nlearned how to make guitars there.

I think some of the most important innovations,

the definitive innovations\Nin the evolution of the guitar,

have been given above all by Agustín Caro in Spain. What is the\Nthe contemporary bridge, the elevation of the neck, and the reduction of the

double strings to single strings.

And some more.

So, he’s not very well known,\NAgustin Caro,

we don’t have any biographical information about him,

we only know his first name and his first surname.

We don’t know anything else. But he’s a guitar maker\Nvery, very important. That then Caro influenced

a lot on José Pernas and José Pernas had\Na lot of influence on Antonio de Torres

I think so.

Well,

Romanillos’ work is impeccable.

It’s an amazing work what he did\Ntogether with his wife, together with Marian

And they have achieved a world-wide fame for Antonio de Torres\Nwhich seems to me to be deserved in all aspects. But perhaps they have

remained anonymous, or almost anonymous,

other very important makers, such as\Nfor example, Pernas and Agustín Caro.

And in the Granada school there are more.

In fact, my doctoral thesis in musicology\NI did on the Granada school of guitar making,

the old Granada school,\Nnot the 20th century, but the previous one until the end of the 19th century.

And there I try to give a little bit of all these clues\Nand I continue the research, because I think

that it’s worthwhile for people to know about this.

That there’s scientific work on this.

And then there are also other very important makers…\Nbecause Torres worked in Seville with Gutierrez.

with Manuel Gutierrez, who is also very important. Even\Nsome of the guitars that Gutierrez started

Torres finished them. And there are some\Nguitars that were made with Torres’ materials.

There are some necks, that are typical of\NGutiérrez guitars in authentic Torres guitars.

Romanillos I think it\Nclearly states that Torres worked

with Gutierrez or that they had a relationship. The same\Nalso with Manuel Soto y Solares

in Seville, they had in Calle Cerrajería,

they had their workshops almost door to door with Torres

And it is known that sometimes it is said that some of the guitars\Nof Soto Solares were sold by Torres and some guitars by Torres

were sold by Soto and Solares. There is a direct relationship

and that can’t be forgotten.\NBut I don’t want to play down the importance of Antonio de Torres.

His figure is enormous.

Torres worked very well, but Torres also\Nmade guitars that leave a lot to be desired.

I remember a quote from Domingo\NPrat that I find funny:

“Torres made a lion, several cubs, and many junk”. (playing with Spanish words and meanings)\N”Torres hizo La Leona, algunos cachorros y muchos cacharros”

So you can see that Domingo Prat was not very…\Nalthough he bought a lot of guitars by Torres.

and sold in Argentina … but he also knew that…

Antonio de Torres had to eat and was\Na guitar maker that he was ruined several times with business

outside from building guitars, and he had to make\Ngood guitars, regular guitars, and very cheap guitars.

There are examples of very cheap guitars\Nwhere you see very good workmanship,

but sometimes the materials look a bit disappointing let’s say.

I don’t think the business\Nwas that kind to dothat,

for there to be subcontracting.

It is possible that some guitar makers, as in the case\Nof Hermanos Moya,

worked with him or had a relationship with him.

But I don’t think that neither in his first\Nnor in his second period

was the business so flourishing\Nto have employees and subcontractors.

It’s not like, for example, workshops in Valencia or Madrid where there were\Nworkers, apprentices…

where there were a number of people working for the name

of the owner of the workshop

Torres, I think he worked alone, more or less, as we work here,\Nas we work in Granada.

each one of us, in our workshop, we make our own guitars\Nwith our tools, and we don’t have… there’s no

apprentices, there’s no system like that, there’s no such thing as a guild or anything like it.

So this is the culmination of a\Nformative process at the University in my studies of

musicology in the University of Granada, and after several years\Nof research, I presented my doctoral thesis

on the Old Granada school of guitar making,\Nwhich unfortunately, there are not many theses

about the world of the guitar and about guitar making.

So, I dedicated myself, well, that’s why, to the\Nold school of Granada that I believe is

very important and it hasn’t been, it’s not reflected,\Nin most of the bibliography.

I do a study

from the history of the evolution of the guitar…

And here I have a lot of data about the 18th century, about guitar makers…

Here you can find a detailed\Nhistory of the guitar.

Its evolution.

Its most important innovations up to the\Npresent day guitar. And the role that I think it played

very important role that the Granada school played in that evolution.

So, some of the most important innovations that

have taken place in the guitar

the oldest instruments that\Nare made by makers from Granada.

A history of the guitar,

first a state of the question is made\Nwhich is discussed in all the bibliography of

the subject of the Granada school.

Then there is also a history of the guitar

trying to put the most up to date\Ncurrent advances on the research of the subject.

And then a system is also proposed\Nof research on antique guitars.

A system, then, a battery of tools\Nand techniques to study scientifically

a guitar and get the maximum information of it.

And then there’s a history of all the guitar makers that we know,\Nthat have worked in Granada

from the 16th or 17th century to the present day.

For example, Romanillos in his book

I don’t remember if there were 120 or 100 guitar makers from Granada that he mentioned\Nand, in the last inventory, I mention more than 200 or 230.

A lot of guitar makers have been found and well, also\NI include the actual guitar makers,

so it’s a complete history, although the investigation

ends in the 19th century

The 20th century I do not include it in my work

Later in some work it can be done.

READ MORE

READ LESS